Metaphorically, Asger Jorn was a bomb-thrower. His art and his opinions challenged cultural norms at a time they needed to be challenged, as the Nazi regime was beginning to take a foothold in Germany and beyond. From his perch as one of Denmark’s most radical modern artists, he defended kitsch by famously stating “the great work of art is a complete banality,” in effect beating Warhol to the punch by at least a decade. Even in 1933, he was upending establishments, publishing a book titled “Blasphemous Christmas Songs.”

The public didn’t appreciate Jorn during his time—such is the fate of the counterculture innovator—and he didn’t sell much art. A documentary about his life is pointedly titled “Go to Hell With Your Money!”

But more importantly, from a historical perspective, is that Hitler very much despised the ambiguity, the primitive imagery, and the flaunting of realist traditions in the art that Jorn and his Danish compatriots were creating in wartime Europe. To the art world, the “Helhesten” movement—named after a journal Jorn and colleagues published, which in turn is based on a Hellish symbol of a horse from Danish folklore—was an important flowering of abstraction and anti-realism that exploded concurrently with the rise of abstraction expressionism in the United States. For the Nazis, it was “degenerate art.”

The NSU Art Museum in downtown Fort Lauderdale happens to possess a trove of Danish art from pre- to postwar periods, and its current exhibition “War Horses: Helhesten and the Danish Avant-Garde During World War II” picks up where last year’s “Spirit of Cobra” show left off. Or, rather, it’s a prequel: The Cobra movement of experimental Scandinavian art rose from the ashes of the short-lived Helhesten. For those who remember the museum’s “Cobra” show, this one may feel like a bit of déjà vu; some of the artworks repeat, and like most revisitations of similar themes, it lacks the eye-opening sense of discovery that “Cobra” proffered.

But what endures, compellingly, throughout “War Horses,” is the idea of an artistic community finding its identity. The artists in the “Helhesten” movement numbered at least baker’s dozen—their most famous exhibition, recreated in this exhibition, is titled “13 Artists in a Tent”—and their disparate temperaments pulled the work in opposing directions. Some favored pure abstraction, others integrated figures; some loaded their work with overt antiwar symbolism, others sidestepped literary readings of their art.

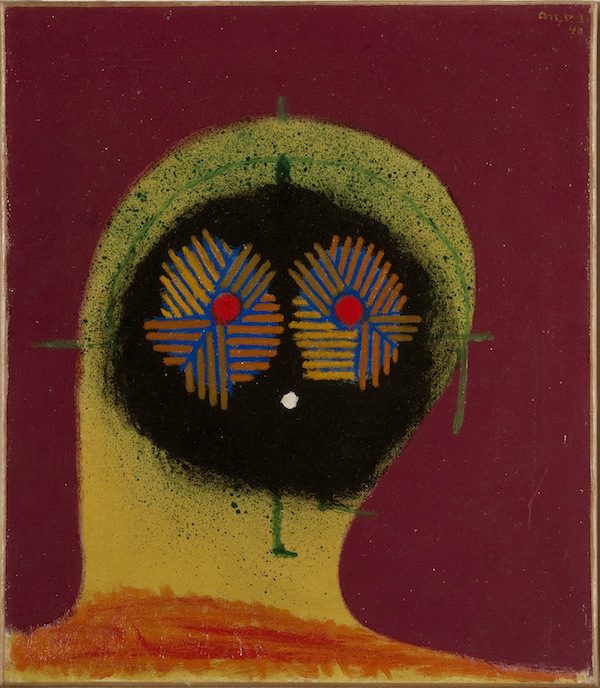

The more you meander through “War Horses,” the more you’ll recognize the distinct approaches of certain artists: Else Alfelt created impenetrable abstract oils, with their woodsy thickets of paint; Egill Jacobsen, with his busy, sometimes overwhelming abstract paintings, was the most Kandinskyesque artist in the group; Jorn favored feverish charcoals and faux-childish paintings of fantastical creatures that tantalize us in their implacability.

The most impressive works are the ones that most directly offered, as one of the exhibit’s taglines suggests, “radical art as resistance.” Henry Heerup’s “War and Peace” is an epic canvas containing both of these opposites: a scene of pastoral family life interrupted by a giant pitchfork (like Heerup’s best work, it flaunts realist perspective), parachuters and warplanes. In Heerup’s “The Bombers,” planes descend kamikaze-style toward a two-headed figure, one head already slain, the other soon to join it. And it’s hard not to read Nazi symbolism into Pedersen’s “The Big One Eats the Little One,” an oil-crayon painting in which a colossal bird prepares to feast on a tiny one.

Then again, Pedersen himself preferred the term “fantasy art” to describe his work, as opposed to the more academic “abstract art.” “Fantasy art” spoke more to the people, and “Helhesten” was nothing if not a people’s art movement. But the choice of “fantasy” also distances itself from the realities surrounding these artists. Could it be that this bold art was intended to be an escape more than a confrontation?

I’m inclined to think it was both. “Helhesten” ultimately works on two levels, as childlike kitsch and political revolution. The hell-horse that dances in Pedersen’s ink drawings might forebode mythic doom. Either that, or a horse is just a horse.

“War Horses” runs through Feb. 4, 2016, at NSU Art Museum, 1 E. Las Olas Blvd., Fort Lauderdale. Admission costs $8-$12. For information, call 954/525-5500 or visit nsuartmuseum.org.